19.01.23 / Daniel Ibbotson

How to choose a design company

Some brief thoughts the best way to select a design company. Or at least what we think is the best way.

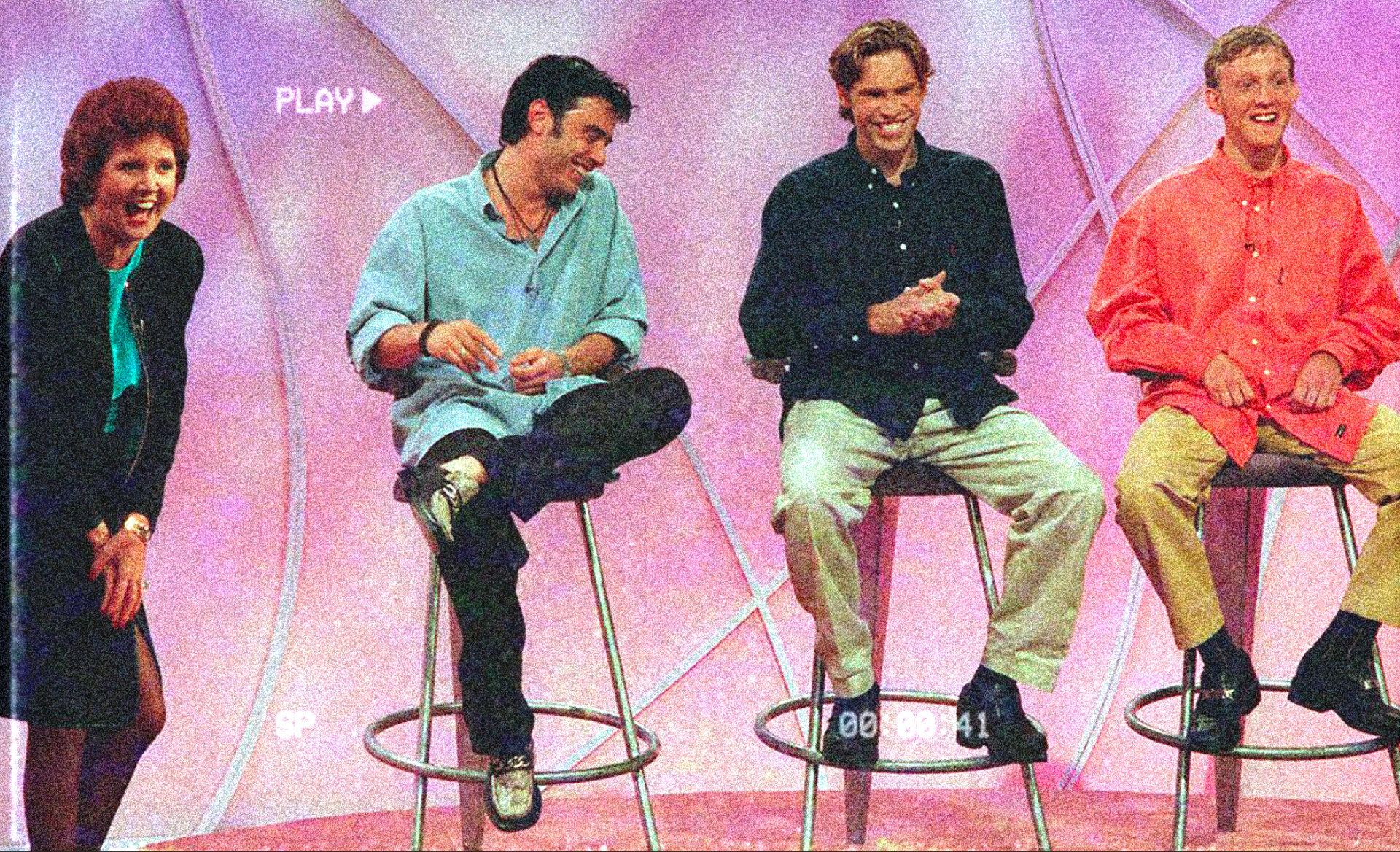

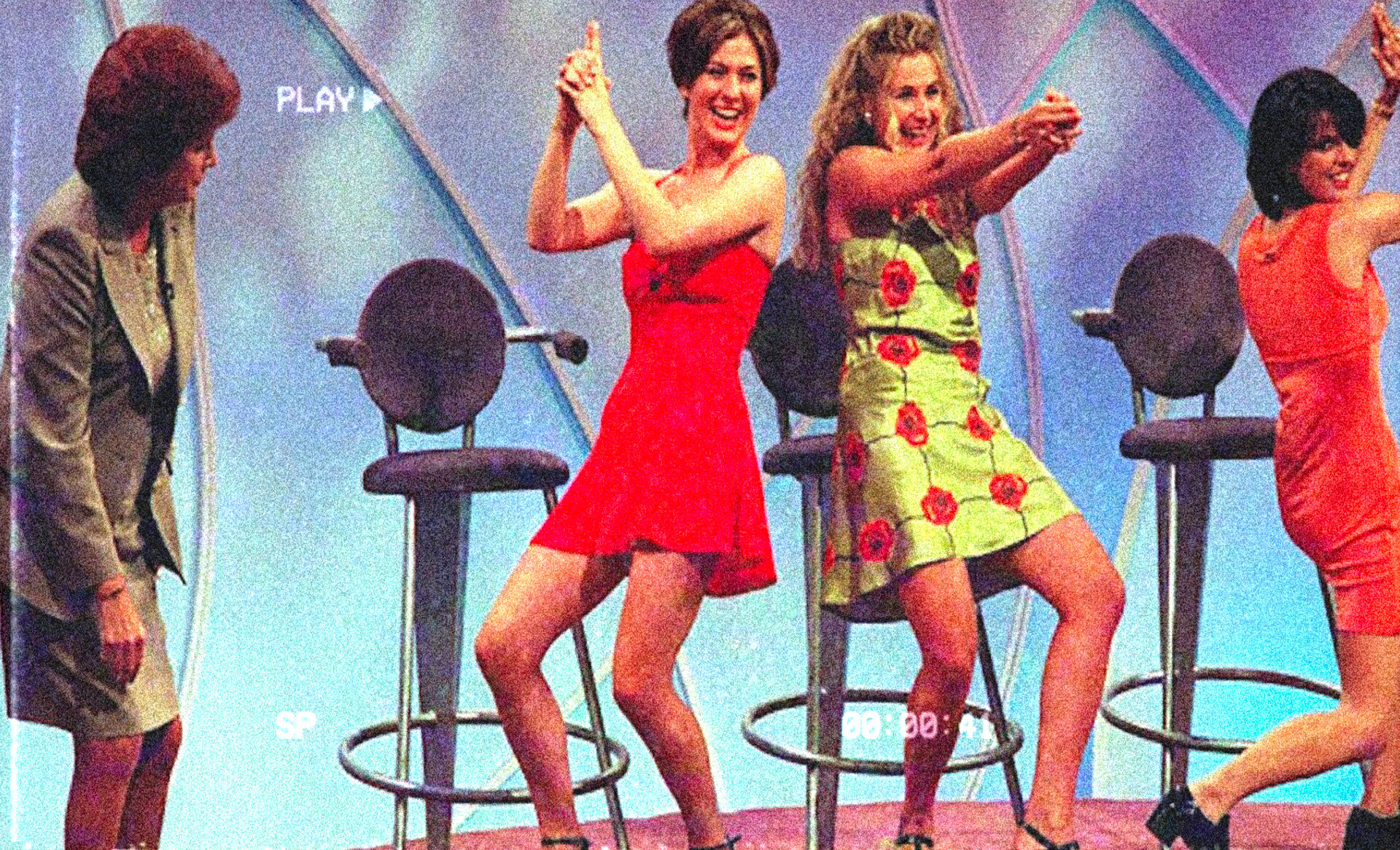

Swipe right.

We win new work in all sorts of ways. Sometimes it’s smooth and harmonious for all parties. Sometimes it’s, well, complicated. We thought it would be interesting, and perhaps useful, for us to briefly talk about the issues from our perspective.

Typically there are four main approaches that clients use to select a design company. The Pitch. The Tender. The Proposal. Or they use research and dialogue to make an informed choice based on a variety of important factors. (I’m sure you can already see where this is going).

The Pitch

We don’t take part in very many creative pitches these days. Only when a project really feels like it would be a good fit. For us, as a small studio, pitches have proven to be an inefficient way of winning new work.

More often than not a creative pitch is unpaid, or at best there is a relatively small sum of money assigned to the process. However it takes a significant amount of time and thought to compete in this scenario. This means that our staff are diverted away from fee paying jobs to work on speculative opportunities for a small fraction of the actual cost of their time. For example the last pitch we took part in offered a fee of £500 but it cost us over £3000 to do the work involved. If you win then you get the chance to recoup your loss but if you don’t then the economics of this are pretty clear.

Aside from the financial aspects and the implied lack of value placed on the process by zero or small fees, the pitch route is flawed in other ways. At best a creative pitch will provide you, the client, with a range of responses informed by the brief you circulated. The quality of these responses will rest heavily on the quality of your brief. A well thought out and comprehensive brief should yield good quality submissions. A bad brief will not.

But whether the brief is good or bad the pitch process removes the most important collaborative tool that designers and clients have. Dialogue.

When we begin a new project we spend a lot of time talking with our client to properly understand their company, their aims, objectives, motivations and their audience. We do this before we begin the creative process because we have found it leads to far more effective creative outcomes. Outcomes that our client feels fully invested in because they have been an integral part of the process.

Quality in design, like all creative forms, is subjective. What I think is great, someone else might think of as terrible. It is very difficult to objectively measure or score a piece of design work. (Above a certain level of course). This means that the response to a pitch presentation is always going to be subjective. What do I ‘like’ the most. What ‘feels’ right.

Un-measurable qualities lead us all towards the things we like and dislike. Our taste. Taste is why smaller client groups or leadership teams often lead to better design outcomes. Design by committee means that there is so much personal taste at play the outcomes can be bland, the least offensive to the most people.

But of course it’s not for you. Nine times out of ten the design outcome needs to be aimed at a specific audience rather than the client themselves. This is a fact that often seems to get lost.

So in a pitch how is the winner chosen? Perhaps you liked their approach to your project and the way the work looked. Perhaps you felt that you clicked with the team, like you would get along and work well together. All important factors. Or maybe you didn’t really like any of the submissions that much but you had to choose one and the winner was the least worst.

Of course usually there will be a set of criteria defined in advance and each submission will be ‘measured’ against these. But what is that measure? How do you judge if Company A scores higher than Company B. How often is that really more than a feeling?

The Tender

This idea of measurement really comes home to roost in the tender format. A procurement process is a great way to compare like for like. Company A has copier paper that is exactly the same as Company B. They are both 80gsm, come in packs of 500 sheets and are FSC accredited but Company A is slightly cheaper. Company A wins. But the quality of design can’t be measured like this. Indeed some high level organisations have admitted that they don’t know how to evaluate design.

Even when companies are tendering for ‘like for like’ deliverables the playing field is not really level. The working process of Company A might involve much more care and attention than the competition therefore their cost might be higher to deliver the same outcome. But that outcome will be better.

Or they may actually have a far better understanding of the context but there is no real way to express this within the restrictions of a tender format.

Or maybe Company B are so desperate to win the work that they’ll submit a crazy cost undercutting the competition and forcing a ‘race to the bottom’ situation that is good for no one, even the client, because at some point Company B are going to want to recoup that loss and will they really deliver their best work at a heavily reduced rate?

There is certainly an ‘art’ to the tender process. Knowing what kind of language will score well, name dropping, ego massaging. It’s sales right? But even though we get to spend hours and hours writing thousands of words to complete a full set of tender documents, the process again cuts off the most critical factor of any creative relationship. Dialogue.

The Proposal

A proposal is a presentation of previous experience and credentials with an outlined approach and budget for your project in response to your brief. It is far less demanding in terms of time for the design company, requiring fewer sacrifices and minimised loss if unsuccessful.

As with the pitch and the tender the quality of the brief is critical, as is the scope. With any of these routes in order to compare like for like the scope of the project needs to be well defined. A website isn’t just a website, it’s a certain number of page templates, certain functionality, content and experiences all living on a certain content management system with associated fees and font licenses and so on. Often it’s impossible to define the full scope of a project at the brief stage because the strategy and tactics have yet to be fully explored.

As designers our understanding and input should and will inform the nature of what you need. This can only be discovered through a process of dialogue. Again this makes it difficult to measure one proposal against another because there is always scope for interpretation on both sides.

So how should you choose a design company to work with? Well, we think it’s like choosing a partner.

What makes for a good partner?

Do they look good?

Does their work appeal to you?

Do they present themselves well?

Do they listen?

Are they able to understand what you want?

Can they satisfy your needs?

Do they provide the services that you require?

Do they have a network to call upon for anything they don’t provide themselves?

Are they experienced?

Have they been around the block?

They don’t have to have already done exactly what it is that you need but you need to feel that they know their way around a project that is in some way comparable to yours.

Are they successful?

Do they have a proven track record?

Are they respected?

Do they deliver results?

Do you like how they sound?

Communication is key.

Do they speak your language?

Do they care?

Do they make an effort?

Is there a sense of pride and investment in what they do for others and what they might do for you?

What do other people say about them?

Do they have testimonials from clients?

You can even ask for references.

Are they cheap?

Or, can they do what you want for what you have to spend?

There is always room for negotiation.

And perhaps most importantly.

Are they fit?

Well, will they be a good fit for you?

Can you see yourself working with them long term?

Do they get you?

Next article