17.11.22 / Andy Graham

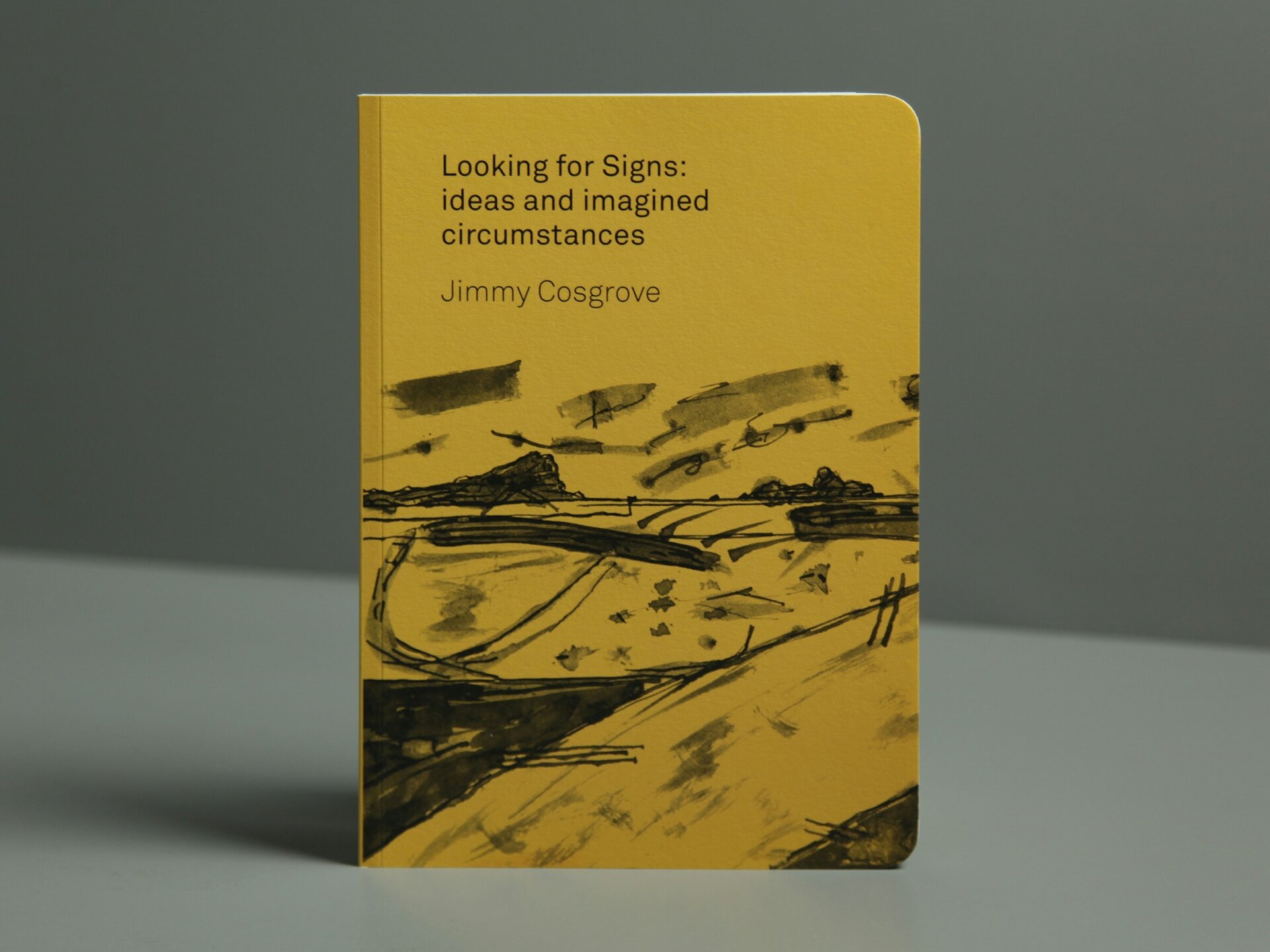

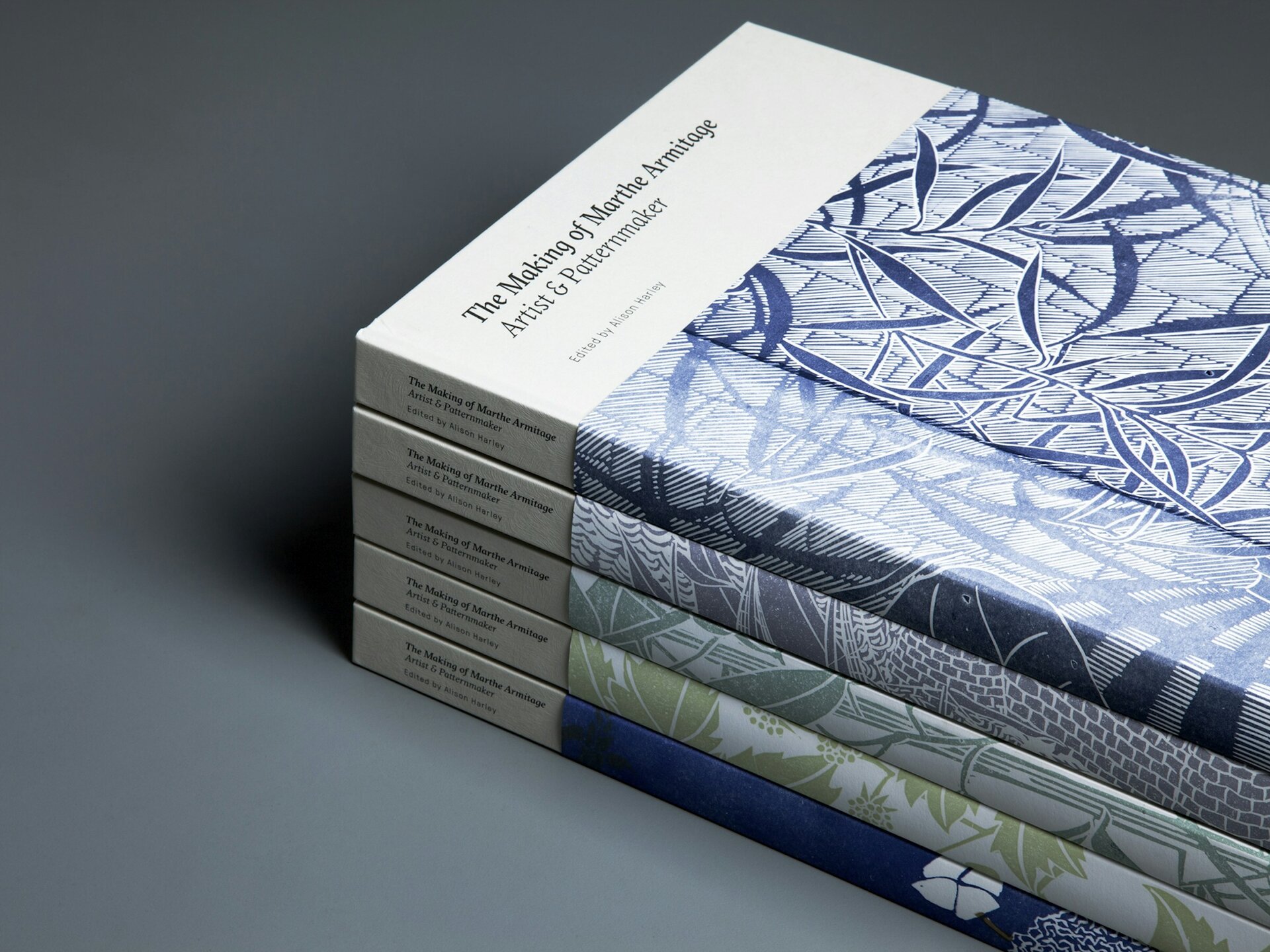

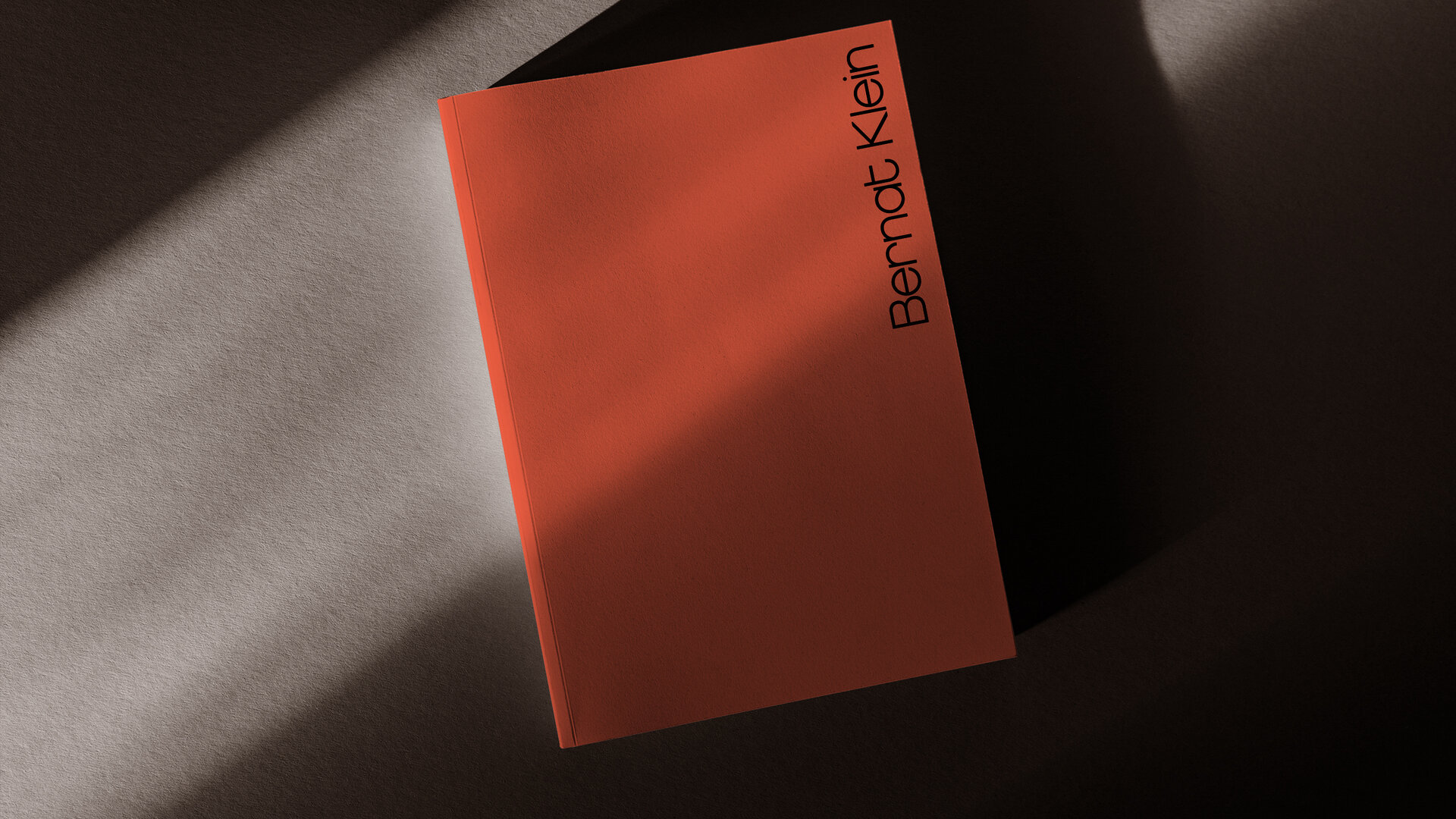

Design of a Klein book

Designing for posterity vs. designing for an ever-changing digital landscape.

Some designers specialise in editorial design but for most of us, these projects don’t come around very often. When they do, it provides a rare opportunity to test those fundamental skills that are at the heart of what it is to design things.

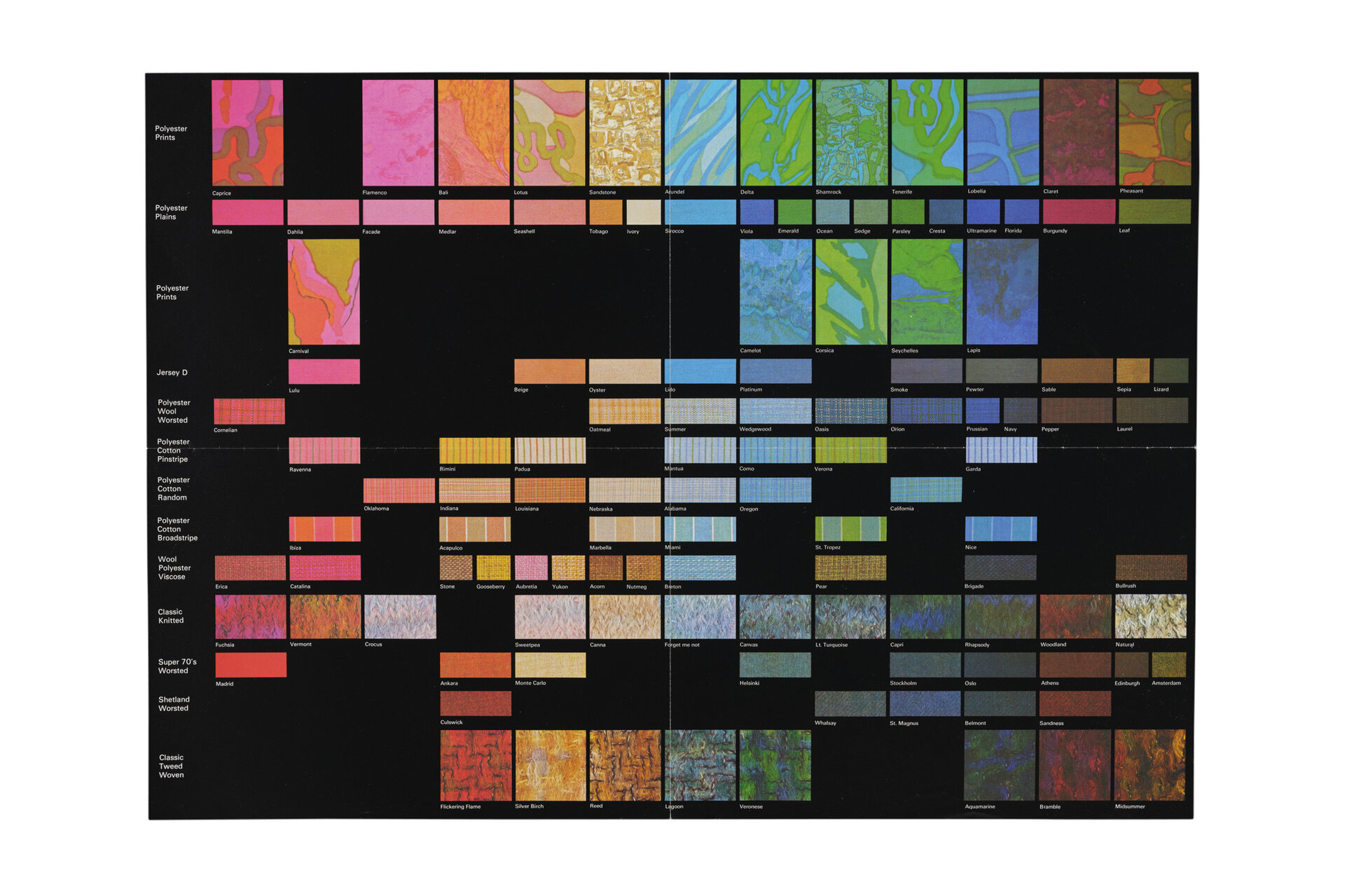

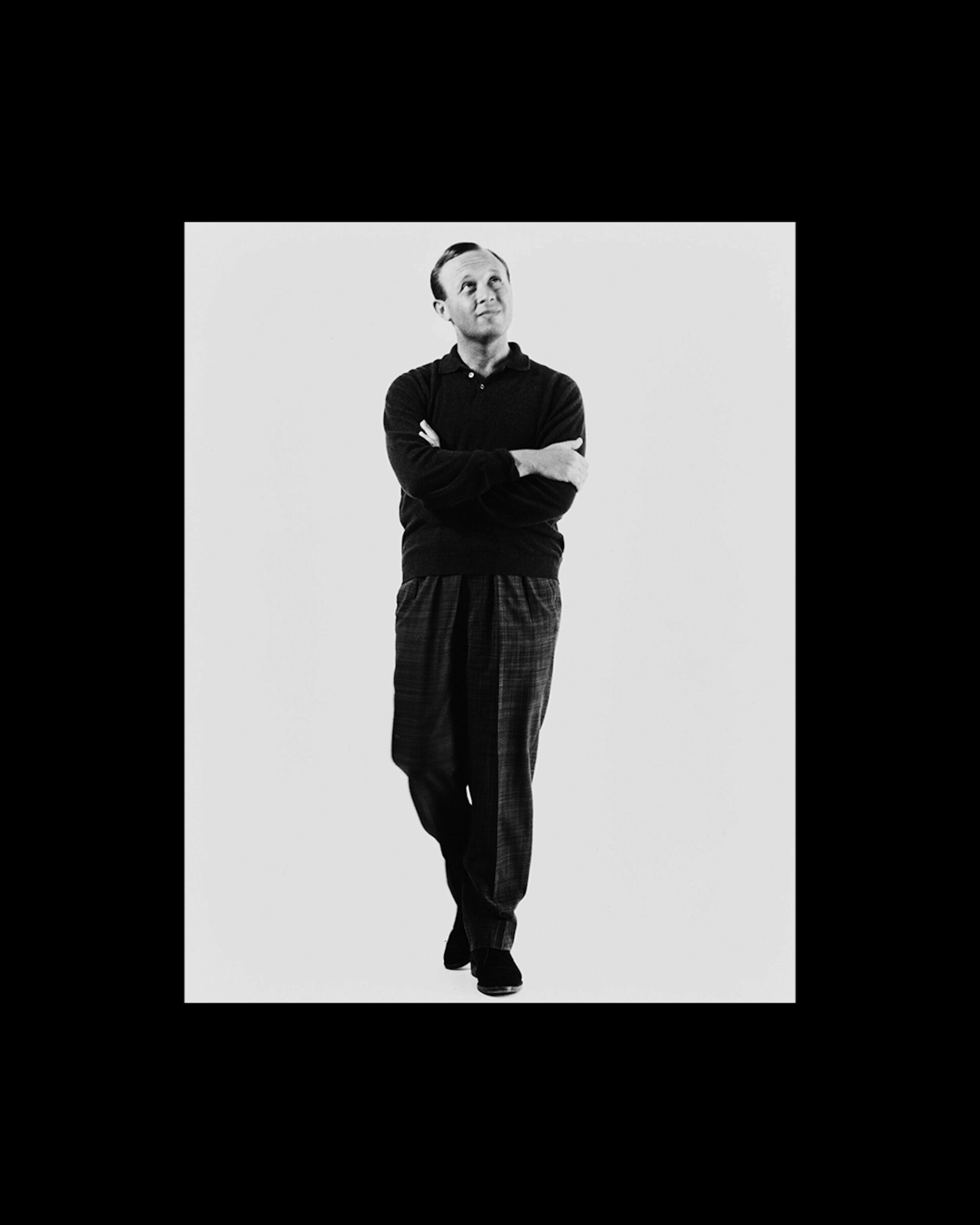

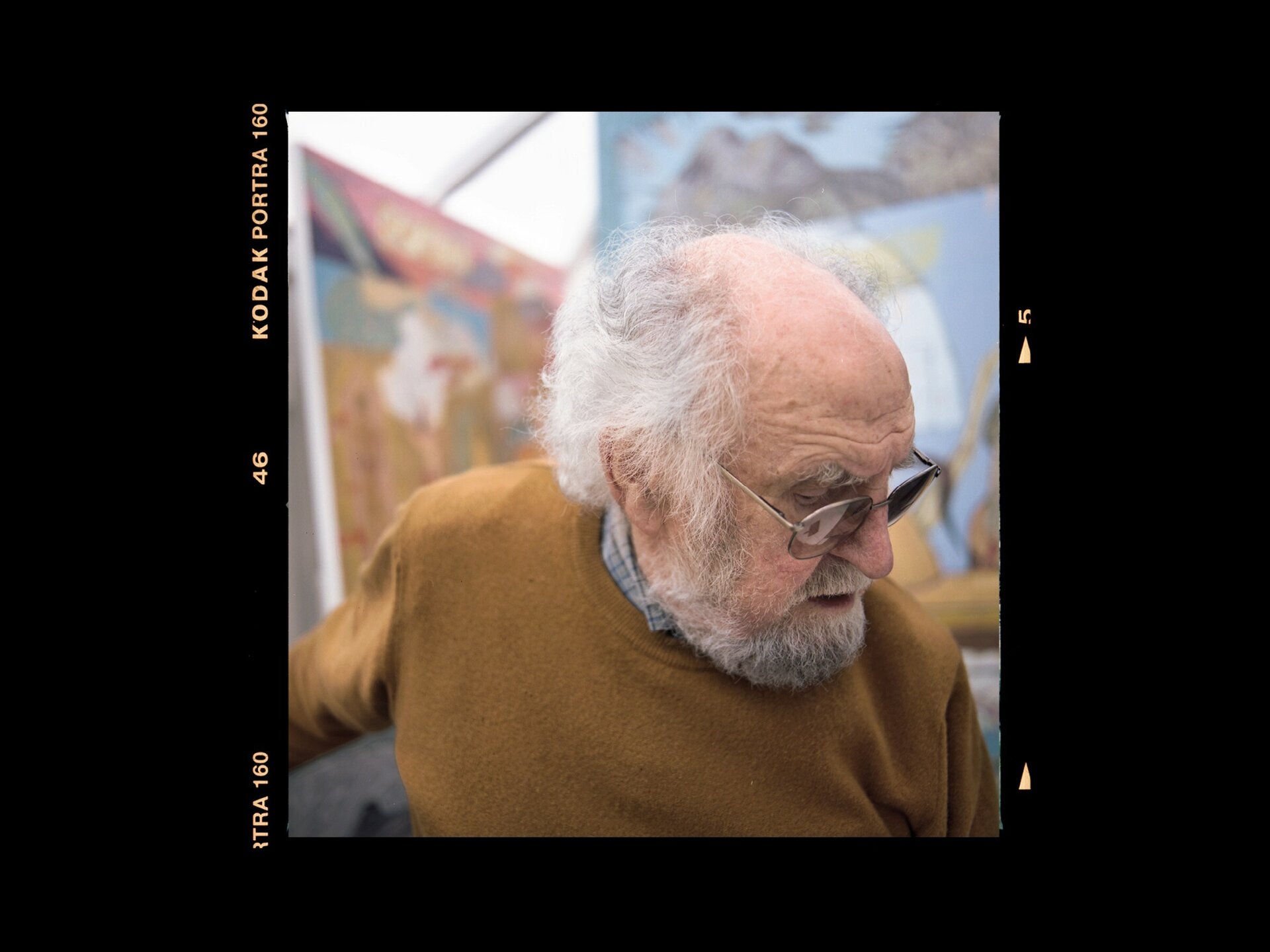

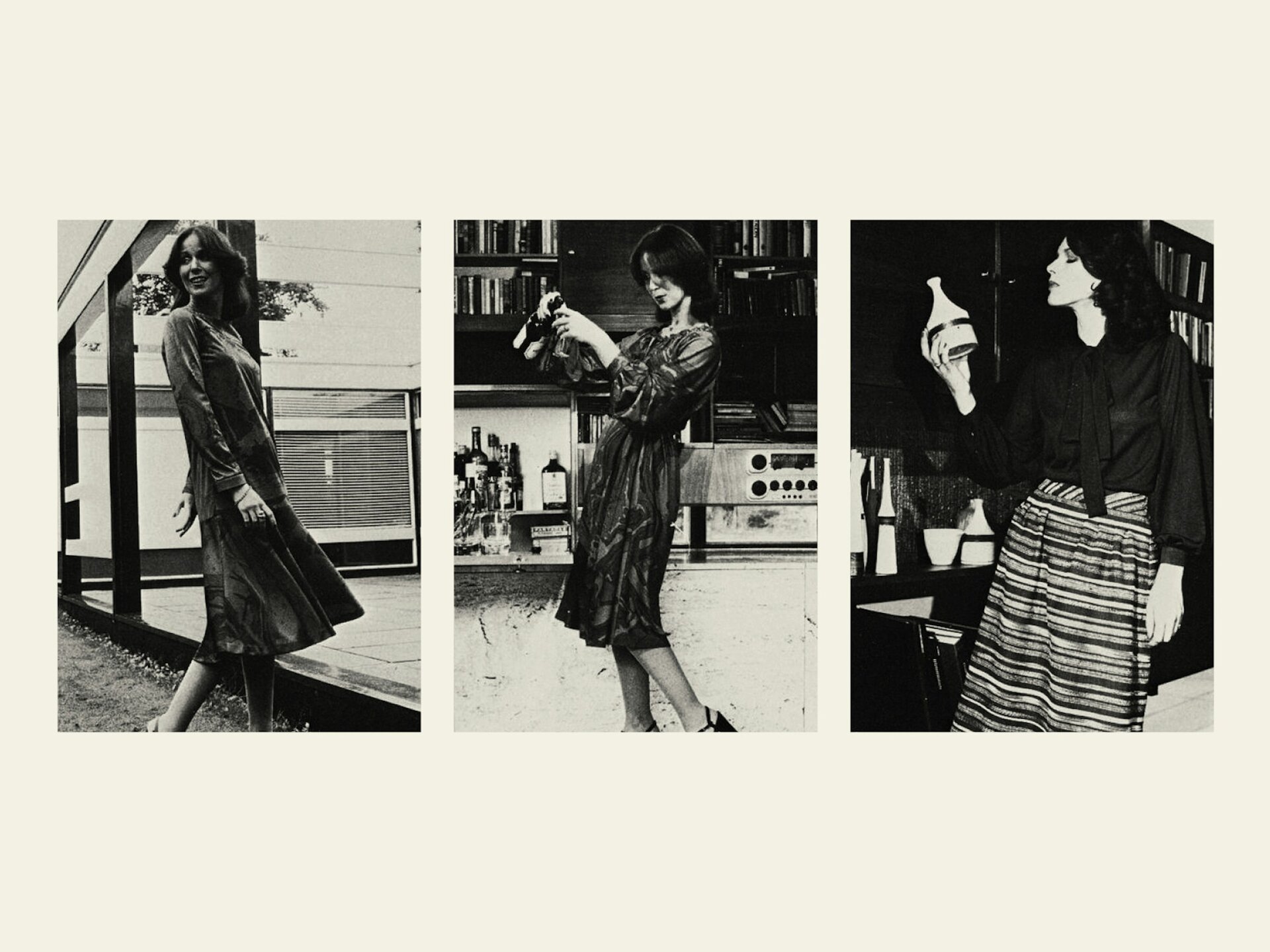

Bernat Klein, a Serbian born textile designer, colourist, painter and all-round polymath was a key figure in the post-war modernist design movement in Scotland. His body of work is vast and eclectic as is his list of professional accolades and achievements.

Klein wrote extensively on design and colour theory. If you read his writing on the subject, he demonstrates a deep knowledge and understanding of the role of the designer, and often relates this to our collective condition and what it means to be human.

“

What matters is to hold, stand by and review informed opinions based on up-to-date facts, arrived at after open, broad-minded consideration. It is therefore important to be educated, cultured, civilised, sensitive in regard to all the senses, responsive and alive. These pennants of humaneness should be flown high for their own sakes.

Bernat Klein

Design Matters, p.97

The book was commissioned to mark and celebrate what would have been Klein’s centenary year. The weight of responsibility I felt working on the project was therefore pretty significant, but not necessarily a burden. I have worked on book projects before where the focus has been on presenting a body of work and celebrating the life of a person. That level of personal investment from the client side often brings with it a certain amount of pressure. It can feel overwhelming.

For me though, the anxiety of decision making is all part of the process. Design is not emotionless and this becomes most apparent when you are so immersed in someone’s else personal life that you have to do them justice! These projects are often personal journeys of reflection (for the subject and their families too) and inevitably stir up all sorts of emotions for those involved. As the designer, you too become personally engaged – you have no choice.

For me, self-applied pressure – not from a client or a boss – can be a positive, and help to create more meaningful responses. The expectation is that you understand the content and deal with it in a sensitive way. Constant questioning, of your own decisions mostly, helps to achieve the best outcome – for you and the client alike. You test and iterate with the goal of creating a finished article that stands up as a suitable and permanent legacy. One that the client and all the other stakeholders will be happy with.

“

… to me design means to enjoy the exploration of new possibilities. It means to take pleasure in finding new solutions to old problems; or to have fun juggling with a number of old solutions until they suddenly click and coalesce into one, beautiful, new solution.

Bernat Klein

Klein 1976, p.3

The project got me thinking about how the process of creating something like a book is a bit of a unique privilege these days.

You are creating a permanent artefact, an object that represents a point in time in a world where everything has become so fleeting or editable by design. Designing for posterity vs. designing for an ever-changing digital landscape.

My role as designer has changed massively in the past 12 years. Technology of course, being the main driver behind the seismic shift, not just in the type of work we do, but the way in which we communicate. Today’s digital landscape is constantly evolving and provides significant new opportunities for communication and engaging with audiences. Design and client requirements move on these shifting sands. Things happen quicker, all at a pace that ushers in creeping but fundamental changes to our day-to-day work practices.

While I embrace the change that technology brings, working on a print project is a bit of a comfort blanket for me. Of course, there is a substantial amount of work that goes in before you even arrive at a format – budget, spec, format options, content auditing, page plan, etc. – but once you’ve settled on it, you know this is your canvas. The physical parameters are set and what follows is a process of crafting towards a defined, fixed end point – a book.

While the design process is simliar, the opposite is true for digital design. The skill here is to allow for multiple eventualities. What you are actually designing is a scaleable system, one that will adapt depending on how the user is engaging with it. Not only that, you are placing content in your designs knowing full well that this content is designedto change. Digital design tends to be about creating a vehicle for ever-changing messaging, rather than the end result itself. So you are driving towards an end result that is never really finished. Digital ink never dries, someone once said – I can’t remember exactly who.

Don’t get me wrong, launching a website does bring it its own sense of achievement. But for me, the finality of delivering a piece of print is unique in the satisfaction it brings. A book is something tactile and 3D(in the traditional sense) that is experienced in the same way for everyone – physically at least. Delivering a digital experience, one that can only be experienced by users through their screens, evokes a very different sense of satisfaction for me as a designer.

Design for print, more often than not, falls into the ephemeral, practical, or promotional category. But these things – once the staple of the design studio – are becoming less and less common, as the shift into digital channels replaces the more traditional methods of communication.

That’s why these projects often become all consuming, as you – the designer – are obliged to quickly establish an intimate understanding of the subject. The choices you make are permanent and you are veryaware of that as you make those decisions. Designing digital experiences and making choices is often tempered by the fact that things can, and arguably should, change and adapt over time.

“

Design means to care about individuals. Or perhaps, it means simply to care.

Bernat Klein

Bernat Klein quoted in Shelley Klein, The See-Through House, p.169

From a personal perspective, this quote really resonated with me, as it sums up the unique role of the designer as the conduit through which the client’s ideas and ambitions flow. Technology, work practices and expectations are always changing, but what remains the same, is the fundamental need to listen, understand, and most importantly, careabout it.

It describes the internal struggle as you wrestle with those minute decisions. Things that the client would never notice, let alone anyone actually reading the book, but when you’re in that zone, you hit a sweet spot with the parameters fixed, everything in place – you now have ultimate control and it becomes a cathartic process of refinement.

Sorting out line turns to get the perfect rag, or at least you think it’s perfect until the client starts to ask why that paragraph looks a funny length. Incessantly kerning page headers, titles… but stopping there because diving into the body text would just be ridiculous… wouldn’t it? Adding a 0.3pt baseline shift to brackets because they never line up, do they?

Implementing secret tricks that you’ve learned. Those incredibly niche nuggets of wisdom, passed on by colleagues over the years that only you know exist – and are completely invisible to the reader.

I’m talking about manually hanging quotation marks outside the text frame using -600 character spacing because let’s face it, using Optical Margin Alignment would be a) too easy, and b) just too, well… automatic. Obsessively omitting those hidden characters – extra spaces or redundant paragraph returns. Menial mini-tasks, all totally invisible in the end product, but indelibly present in your mind as you chip away, aiming to achieve levels of perfection that border on obsession. You’re all in at this point.

The internal dialogue continues…“I know there’s a footnotes tool in InDesign, but I’m not gonna learn how to use that now. Why do that when I can just do it manually, safe in the knowledge I’ll have FULL control” Knowing full well, that when the inevitable amends roll in everything will get knocked out of whack.

This torturous process of refinement, all that internal wrangling, all signals that you care. The agonies and anxieties you experience in the decision making process are all worthwhile knowing that the thing you are designing will become a permanent addition to the world of things, and an enduring documentation of yours and your client’s toil.

Next article