14.03.22 / Daniel Ibbotson

Stayin' Alive

Some thoughts on design and chronic illness

I’ve been thinking about writing this for a long time but have never really quite found the words. A few things have happened recently that have pushed me on, so here we go.

I have Multiple Myeloma, a form of blood cancer, I was diagnosed eight years ago and have been living with it, on various kinds of chemotherapy since. I’ve had two Stem Cell transplants so far and by all accounts I’m doing ok. There is no cure for what I have (yet) but it is treatable and there is a steady stream of new drugs and new ideas. I’m fortunate enough to live literally five minutes away from The Beatson, West of Scotland Cancer Centre and to have Doctors who are at the top of the game for my condition right on my doorstep. I am lucky in my lack of luck.

I don’t talk about this much because it’s not who I want to be. The guy with Cancer. Denial is part of my coping strategy and part of my identity. So why write this? Simple, I’ve been thinking that Design could do better for people in similar situations. But of course this is written through my lens.

Serious illness seems to chip away at your sense of Identity in so many ways. I guess these will vary massively depending on the illness – Cancer, Multiple Sclerosis, Cystic Fibrosis – there are so many and sometimes there is just nothing to be done. But sometimes there is. Here are some thoughts.

First of all I simply find being a ‘patient’ difficult. It’s not part of who I am. It’s imposed on me and frankly I don’t like it. And I’m reminded of it day in day out because I have to take pills or have treatment or make clinic visits or I get letters telling me I have to be extra careful in global pandemics, or whatever. Now my status is measured by a new set of numbers. Para-Protiens, Neutraphills, Platelets, Free-Light-Chains etc. ‘You’re doing great, all your numbers are stable’. Well, that means I’m alive and will continue to be for the foreseeable future but it doesn’t mean I’m doing great. Doing great is much more complicated than staying alive.

Hardest for me have been the physical changes, it sounds shallow but how I look. How you look is a pretty key part of who you are. Myeloma softens your bones, this is how I was diagnosed. Over several months I had suffered with extreme back pain, was losing weight but developing a protruding stomach. An odd combination. Thanks to a smart Physio a switch clicked and I was given an MRI scan.

It turned out there were seven vertebrae in my spine that had collapsed. I am now almost six inches shorter than I used to be and all this height has been lost in my torso. This means I am a strange shape. I have a curved spine, a short, round body and my arms and legs look kind of long. Clothes don’t fit anymore, I am not the standard shape that almost all clothes are based around. It has taken me a long time to figure out how to dress again, to feel as though I look ok, or at least look like me. It’s trial and error as well, sizing throughout the fashion world is certainly not standard. Thankfully ‘boxy cut’ seems to be a thing at the moment!

The good news is that some brands are starting to notice that not everyone is the same shape so hopefully this is an area that’s going to improve. Imagine if this could go beyond just ‘Tall’, ‘Petite’, ‘Oversized’ and actually start to encompass the specifics of a person’s form. A simple garment like a T‑Shirt will almost always be too long for me, imagine if I could choose from short, medium or long versions? Made to order, tailored almost? The technology exists but the logistics are complex as is the design process of course. Some brands are almost there, like Spoke, who offer real customisation to their trousers. Unfortunately they’re just not really me.

Then there is how the disease has affected what I can do. Actually it hasn’t really. For example, I’m a mountain biker and have been for a very long time. I’ve been on two wheels since I was a kid. This is certainly a big part of who I am and it’s important to me in many ways. My much shorter torso means my organs have a lot less room, in turn this means my lungs have to reclaim space from all the other stuff when I need them. It takes me longer to get warmed up basically but that's about the worst of it. It’s really the treatment that has affected things.

I’ve been on chemo constantly for the last eight years, various combinations of drugs, some more effective that others, some with worse side effects. This last year has been particularly difficult. A year ago I was in pretty good shape but now I’m a wreck. For whatever reason my current combination of drugs has left me open to a string of viruses and infections that have taken me out of action over and over again. Gradually you lose fitness and getting it back just gets harder and harder. (They say you lose a month's fitness in a week of not exercising). It’s always a balance between the pain and the gain. How good are the drugs, how bad are the side effects.

So I find myself back at the start, having to get fit again, from scratch. Not being able to keep up. This is fine, I don’t mind the effort, except that in another couple of months something may happen again to keep me off the bike and I’m back to square one.

In a way Design has already solved this particular problem for me, in the shape of eBikes. Across the board eBikes are taking off and they are getting better and better. Particularly with Mountain Biking they open up much longer rides for the fit folk but the key is they also offer people with physical issues the chance to just get out and ride when otherwise perhaps they wouldn’t be able to. Anyway, I can feel myself sliding towards this category but, for the moment at least, it feels a bit like giving up and I’m not quite there yet.

As I write this I’m sitting in a hospital room having been here all week after a simple cold got out of hand and gave me an absolute kicking. I feel fine now and the twitchiness has started. I need to go home to my family but have three more days of IV antibiotics so I have to stay here. It’s now that the experience starts to gnaw away in other, more subtle ways.

Over that last eight years I haven’t had to spend too much time in hospital really. Lots and lots of clinic visits and day visits for chemo but not much residential stuff, just a few longer stints of three or four weeks. The thing is there is a balance here, one between function and well being. Of course this is not a clear line as, to a point, function IS well being. Infection control is important so that patients don’t actually get ill from being hospitalised. To me though things feel very much weighted towards function. Every single hospital room I’ve been in has been exactly the same. And I mean exactly. The same stuff, in the same colours in the same places relative to one another. (To be clear this only covers only two hospitals, but also two of Glasgow’s newest. And anecdotal research tells me this is not isolated).

When I was admitted earlier in the week I was pretty ill and ended up moving through three different wards. By the time I woke up I had no idea where I was in the building because the room I’d landed in just looked the exact same as the one I’d started in. And the room is not nice. It’s practical, easy to clean, and hard wearing. But it feels cold and institutional. None of this matters when you feel like shit and are full of drugs and tubes and what not. But once you’re over that stage and you’re in the ‘wanting to go home phase’, which lasts much longer, then it starts to wear you down.

My experience is that if you are a day patient you are sorted, there are nice gardens and cafés and what not. But if you are an in patient or even worse confined to bed or perhaps just your room then things are not great. Not to be dramatic but in many ways it’s not dissimilar to prison. The rooms all look the same, there is nothing personal, often there is no view, there is no privacy and you are not in any control of what you do or when you do it. And it’s noisy and bright all the time so sleep is difficult.

I know there are valid clinical reasons that contribute to most of this but still. If you are trying to get better it doesn’t help, over time you start to merge into the environment, lose yourself.

Everything you can see and touch is there to keep you alive, not to help you live.

Individually the products in the room have been well designed to do their job. The layout makes sense from the point of view of medical staff. There is a logic at play. But it doesn’t feel as though anyone has stopped and asked ‘hey, how should the patient feel in here’?

Graphical House has been involved in a few hospital projects over the years so I know that consultation happens. I know there is a budget for ‘Arts’ created to enhance the spaces. (There is stuff to unpack here like why not just spend more on making the spaces better? Great design doesn't have to be expensive). We’ve even been involved in a couple of these and we did the absolute best we could within the mind boggling restrictions. But usually these are all communal spaces, not the ones where the real hard time is spent.

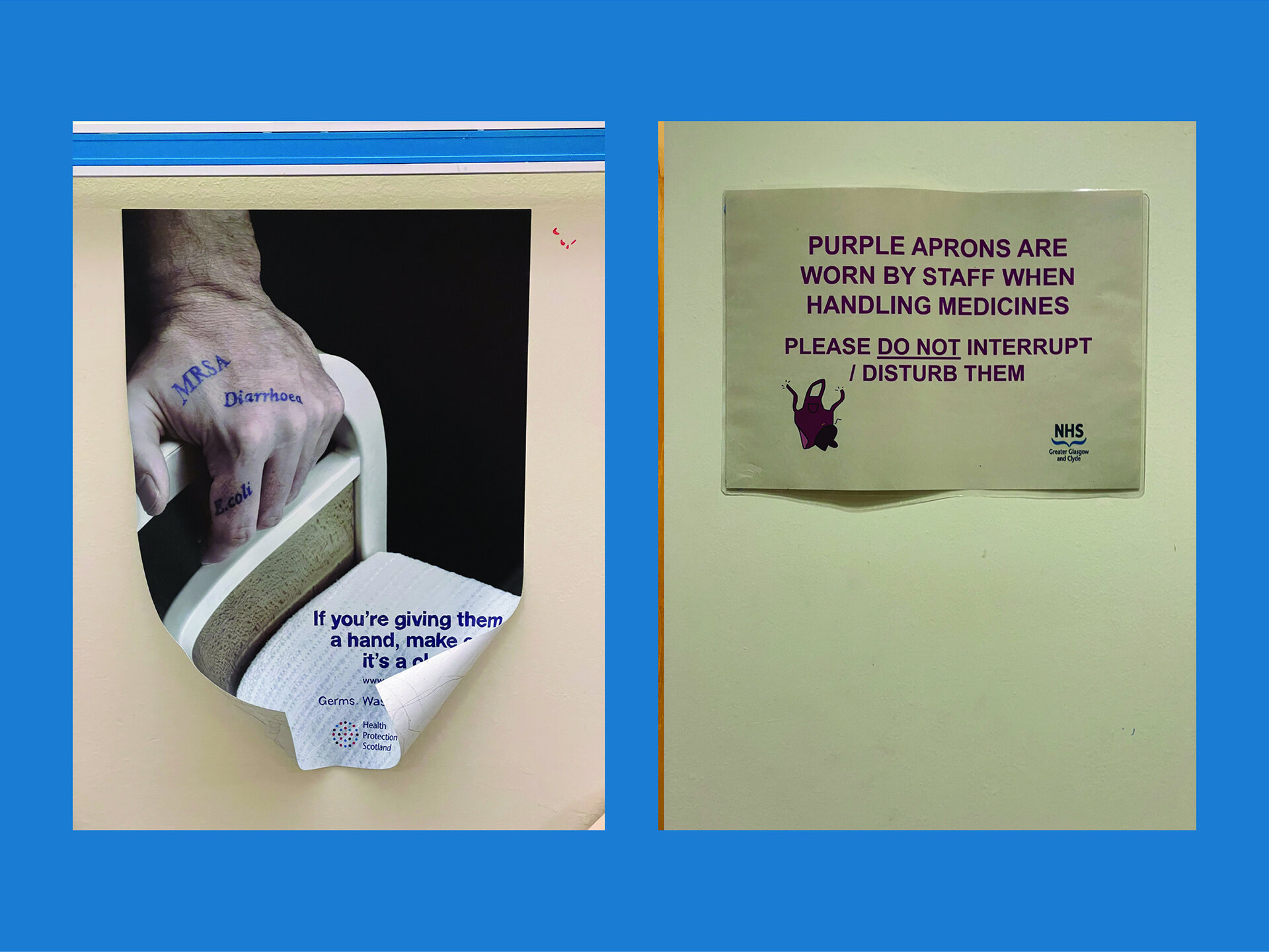

In my experience the real hard time of having a serious illness is when you are alone in the same room for days or weeks or months on end. Away from the people who you desperately want to spend as much time as you can with. Sitting in the chair that is not your chair or lying on the bed that is not your bed. Looking at the same three walls and the same fraction of a view (if you are lucky), through a window that doesn’t open. The same A4 print outs that have been chucked together in MS Word reminding staff to wear a mask or some other nugget of health and safety wisdom. The same machines that are designed to check that you are still alive and to fill you up with the drugs that will keep it that way. The TV that doesn’t work. The paint colour that has been chosen because it’s the exact shade that has been averaged out to show the least evidence of spills of god knows what. The clock with flat batteries that haven’t been replaced because it’s too high to reach without a ladder. The access hatches and air con units and sockets and cables, so many cables. And everything is wipe clean.

In these long moments nothing is about you. Everything is about your illness and gradually the two grow together. Who you are becomes what you have. This isn’t good. I am not my illness. My illness is an inconvenient thing that I have to deal with everyday. Like traffic, or VAT or my neighbour's parking. It is separate to me.

This is not a dig at the NHS. The NHS is incredible and is staffed by the cleverest, most caring, thoughtful, hardworking and empathetic people I’ve met. If this is a dig it’s at designers. Yeah it’s difficult, procurement is a flawed process, budgets are terrible etc. etc. But this is what Design does. It solves problems. So can we not try harder to solve them for the patients as well as the nurses and cleaners and doctors and everyone else. Help the patients to live, not just stay alive.

Next article